Learning Resources

Beekeeping wisdom is often learned by example through mentoring. While this wonderful time-honored tradition still exists, sometimes a quick reference picture is all you need before you ask your mentor to visit your hive yet again.

The following pictures are to help new beekeepers understand what’s going on inside their hives, both to see what a healthy hive looks like and to know some of the problems as well.

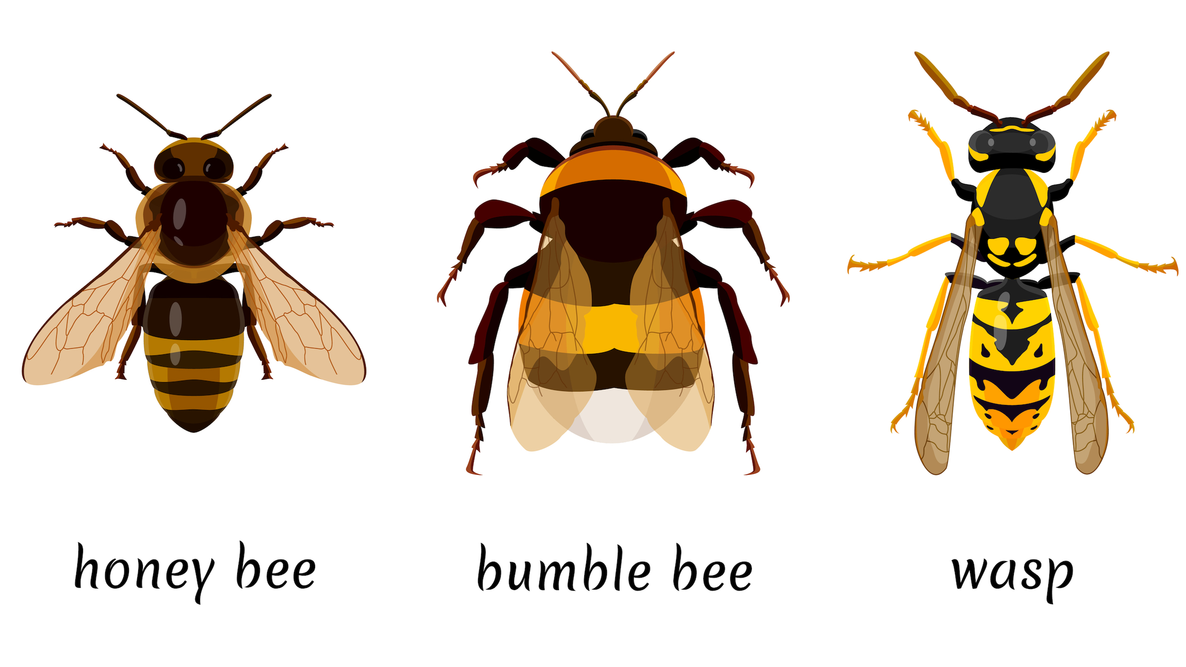

Trying to find out if you see a bee or a wasp? It’s harder than you think when they’re flying, but once they land, their differences are easy to pick out. Use this Wikipedia entry to get up to speed quickly.

If you’d like honey bees removed from your property, you can find contacts on our Swarm Catching page. If you’re looking for wasp removal, try Beverly Bees who will remove wasps for a fee.

Starvation

Bees can starve for a variety of reasons, but one sign they have is a hive full of dead bees with many of them sticking “butt out” in the comb cells. They do this as they are so hungry that they bury themselves in each cell as they lick every last drop of honey out of a cell. While heartbreaking to see bees that have starved, this can even happen when there are other sources of food in the hive, such as sugar the beekeeper has left just inches from their winter ball.

Wax Moths

Wax moths, officially called Lesser wax moths, can take over a hive, but only a weak one. The moths like the dark, enclosed spaces of the beehive, but are usually killed by a reasonable strong colony before they can take hold. In this picture, the hive had died, and the wax moths had moved in. The telltale signs are easy to spot: white webbing throughout the comb and wax moth pupa (think: stubby worms) that are an off-white color. The pupa is larger than you might expect, often being thicker than a pencil, and can move over a few feet in a minute. The picture on the left has a pupa in the lower center of the picture. Don’t mistake the white webbing for a spider’s web, although there may be spiders living with the wax months as well.

Once your hive has wax months, getting rid of them is easy in New England climates. First, scrape off any traces of the worm from all parts of the hive (woodenware, etc), rinse them with water, and throw out any comb that has been touched by the moths. Then, make sure the hive parts are exposed to sub-freezing winter temperatures, such as an unheated garage, for at least 30 days – all winter if possible. Wax moths eggs can’t survive in sub-freezing temperatures, but you want to let them try and hatch and then and die in the cold. By the Spring, any wax months eggs, which can be buried in wood frames, will have been killed, and the hive parts should be OK to use after a good inspection and rinsing them with water.

Queen Cups

When a colony doesn’t have a queen or the queen isn’t laying well, the workers begin to create a new queen. This is done by creating a Queen Cup for each new queen, a special cell for rearing the larger queen. Queen Cups may appear anywhere on the comb but are often seen hanging down from the comb’s bottom edge.

The existence of a Queen Cup doesn’t always mean a new queen is being raised, as they may be created and torn down over a few days. Only when many Queen Cups (usually six or seven) are created and filled with larvae, can you be sure the workers are raising a new queen.

Laying Worker

Look closely at the cells on the left and you will see multiple eggs in a single cell. We can assume these are from “laying workers”; female worker bees are laying in place of a laying queen. While the laying worker’s eggs will grow into a bee, they only grow into drones, so the colony becomes locked in a vicious cycle where no more female workers are born, and thus the colony is headed for death.

There are no guaranteed fixes for this, as even introducing a new queen may not work.

Some beekeepers shake all the bees onto a white sheet 50 yards from the hive and let them all fly back. The idea is that since a laying worker can’t fly, only the non-laying workers will return. They will then sense they need a queen and will create one, or you can introduce one.

Some beekeepers keep adding in frames of brood laid by the queen of another hive, hoping to offset the balance of the laying workers. This is usually done over and over until the workers create a new queen. Then of course she needs to mate, return to the hive, and start laying.

American Foul Brood (AFB)

AFB is immediately identifiable when opening the hive – the smell gives it away. Instead of the normal warm wax smell, there is a smell of rot. Examining the frames of brood will show larvae that have died in their cells, and look black and often curled. The brood pattern should be shotgun due to all the cells that the nurse bees are trying to clean out.

This disease can’t be treated and is very infectious to other bees and infected bees and their hive should be burned ASAP. It is not a danger to humans.

If you have a confirmed case in a colony, use a pair of rubber gloves and seal the hive so that the bees are unable to escape. Then move the hive out in an open area, away from your other hives, setting it off the ground, perhaps on bricks or concrete blocks. Burn the hive with any method you see fit, but the bees and the hive equipment itself must be burned to kill the AFB virus. Any tools that you use to inspect the hive, as well as the rubber gloves you were wearing, should be thoroughly disinfected in bleach.

AFB is not a disease to be taken lightly. Please take all precautions to prevent it’s spread.